Evaluating multivalued functions by square root expansion

In the previous chapter on Image Preservation of Multivalued Functions we saw that instead of evaluating on the -th roots of unity, we can transform into a multivalued function and evaluate it on the domain .

Unwrapping Square Roots

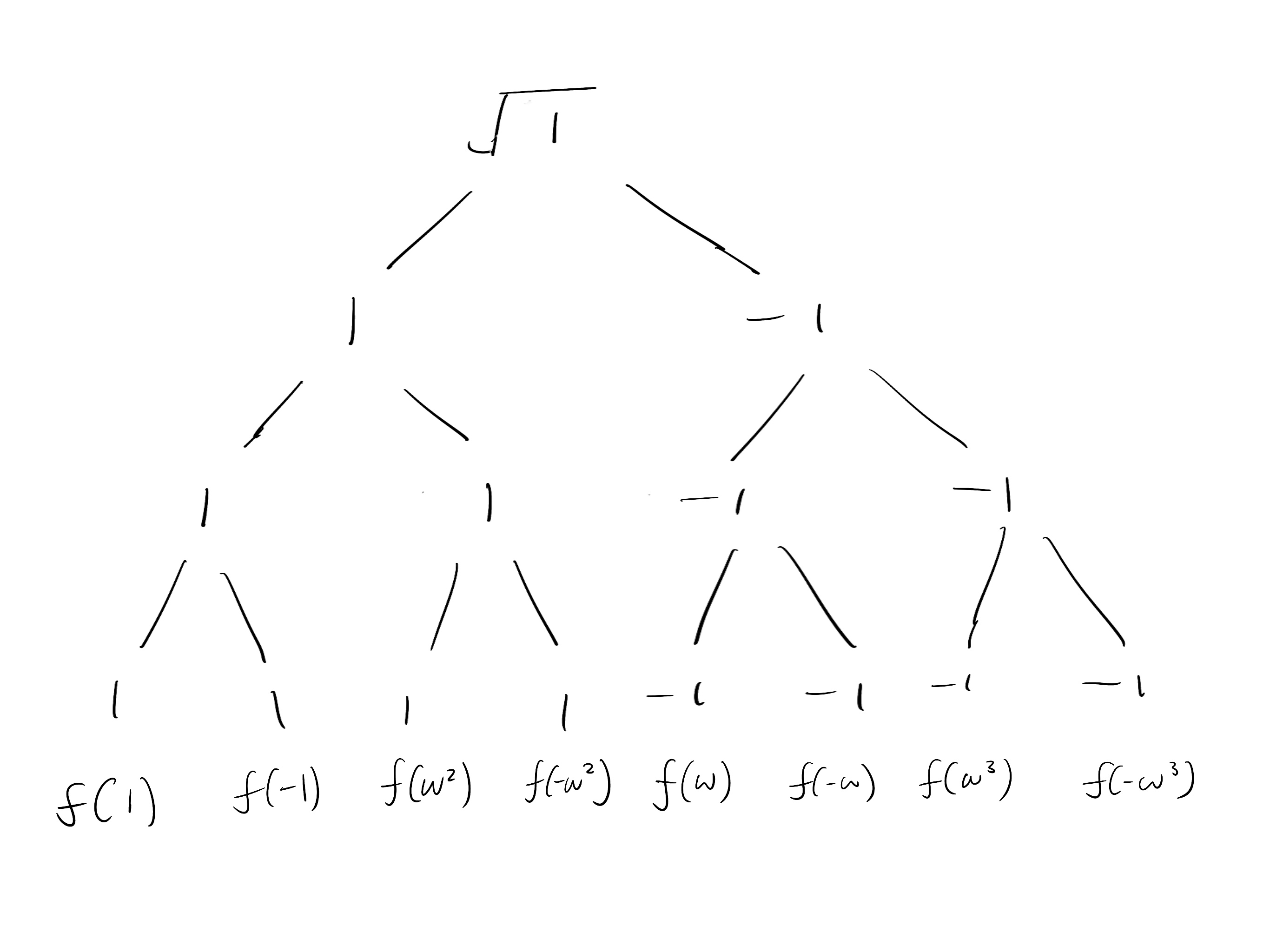

It’s much easier to think of the 8-th root of 1 as nested square roots:

We now show how to evaluate:

using square root expansion.

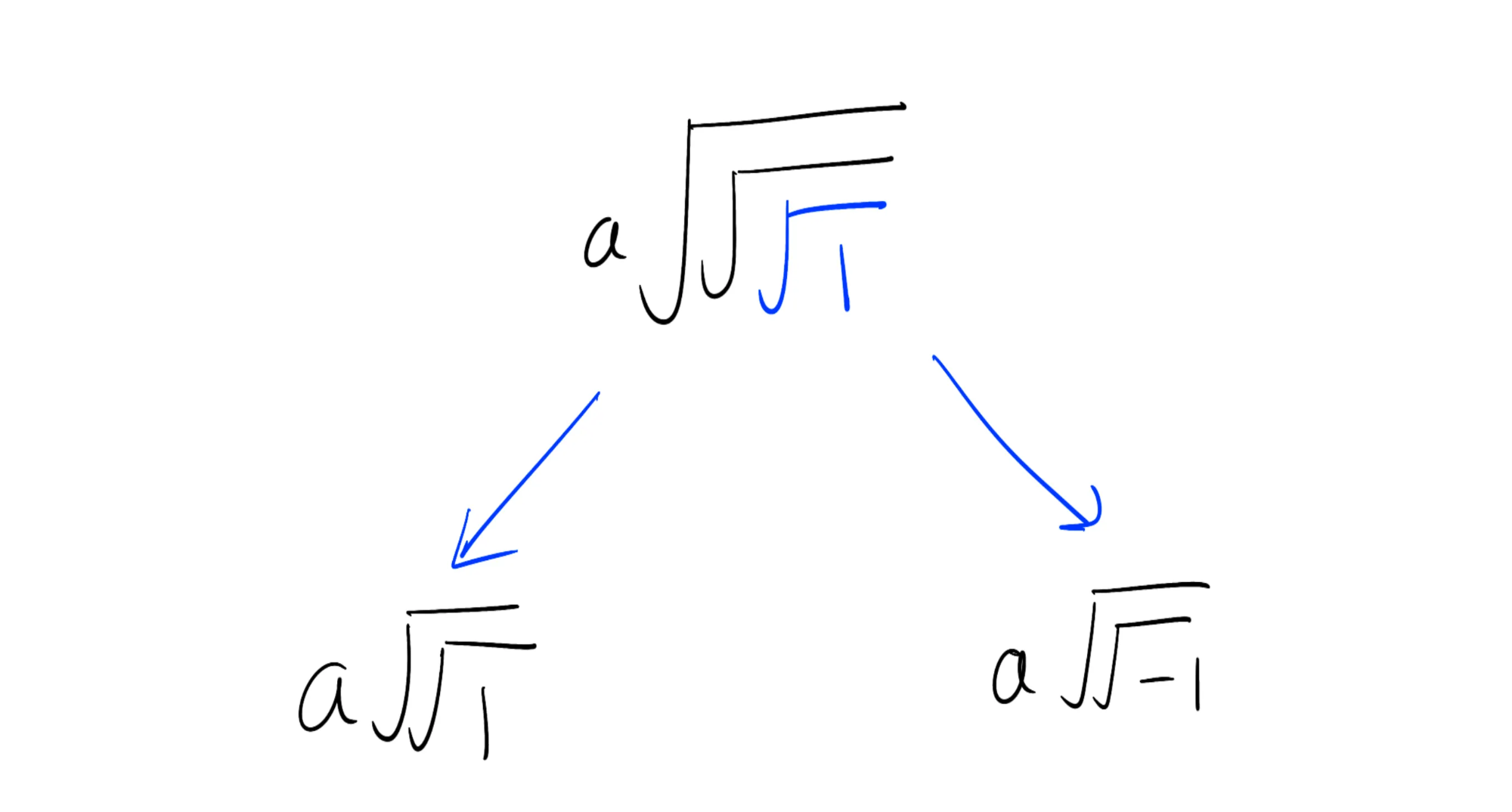

We know that evaluates to so we replace the inner-most square root of 1 with its evaluations:

This “removes” one layer of square roots. Next, we evaluate and . Since we are working with the 8-th roots of unity, so

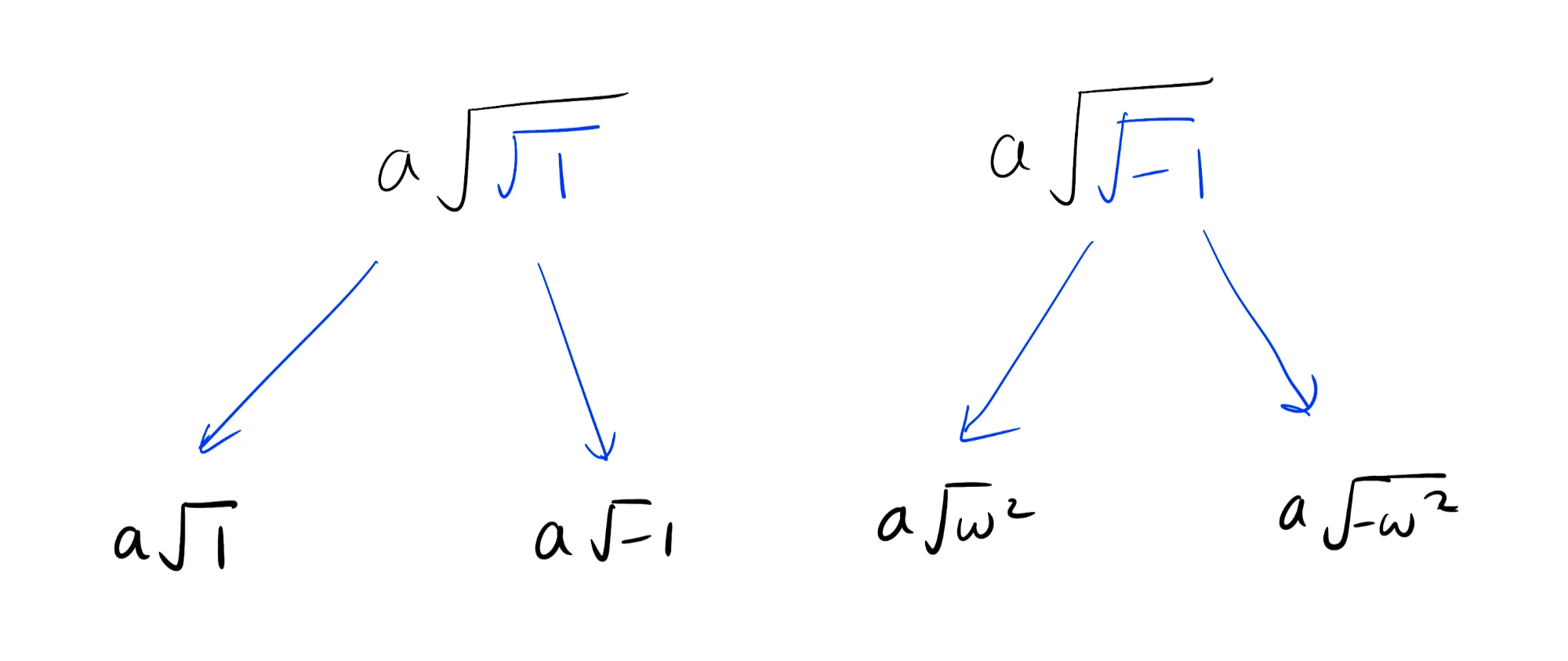

Then, we evaluate each of the remaining square roots:

Observe that the “leaves” of the evaluation tree are exactly evaluated on an 8-th root of unity.

Evaluating on the 8-th roots of unity

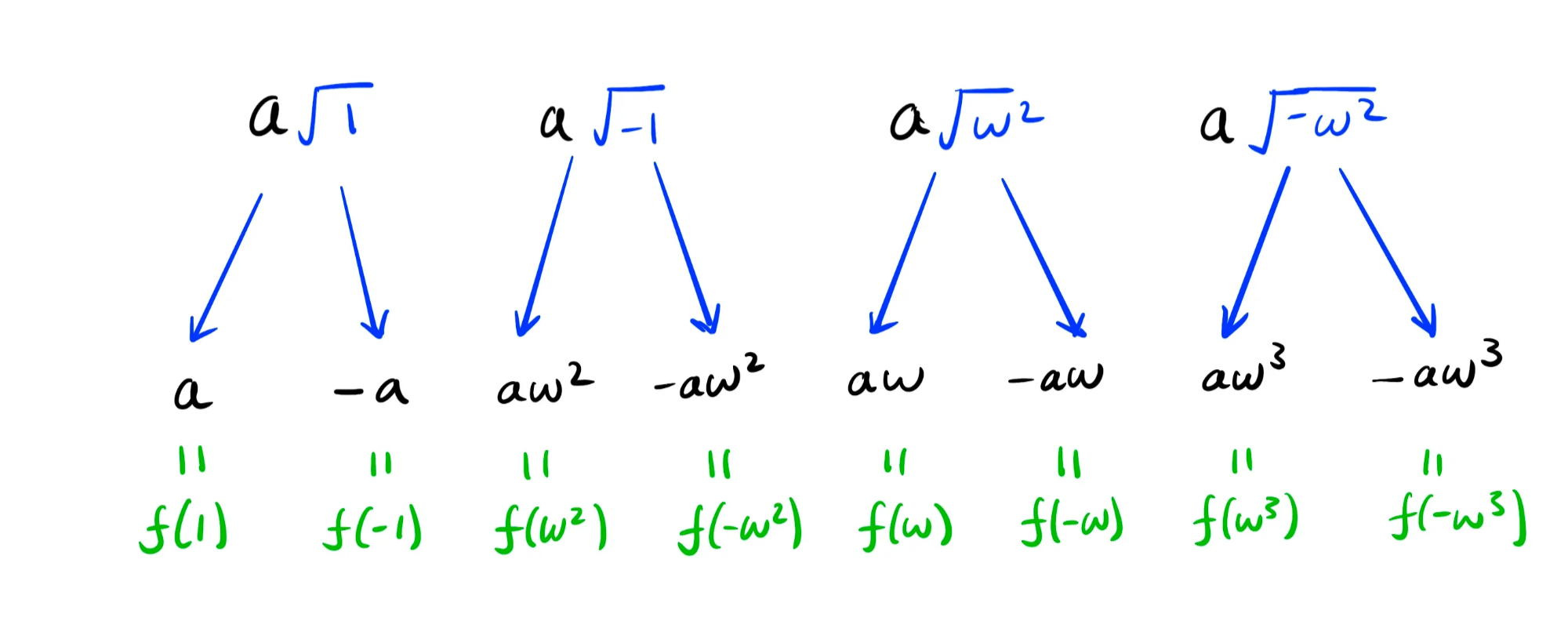

The nice thing about square root expansion is that for most powers of , the square roots “disappear early” as this example shows. We replace with , but since is squared, we have end up with or

Here is the evaluation tree from repeatedly expanding the square roots until we have eight evaluations. In the final row, when there are no square roots, we simply copy the values down.

Now observe what happens if we evaluate the 8-th roots of unity directly on — the outcome is exactly the same.

Evaluating on the 8-th roots

Again, we replace with which gives us . Since we only have one square root, we will only expand the square root once, then simply copy the results down.

We saw in an earlier chapter that is 1 if evaluated on an even power of and -1 otherwise. The result here matches the expected outcome.

Evaluating on the 8-th roots of unity

If we replace with , we get a slightly awkward result:

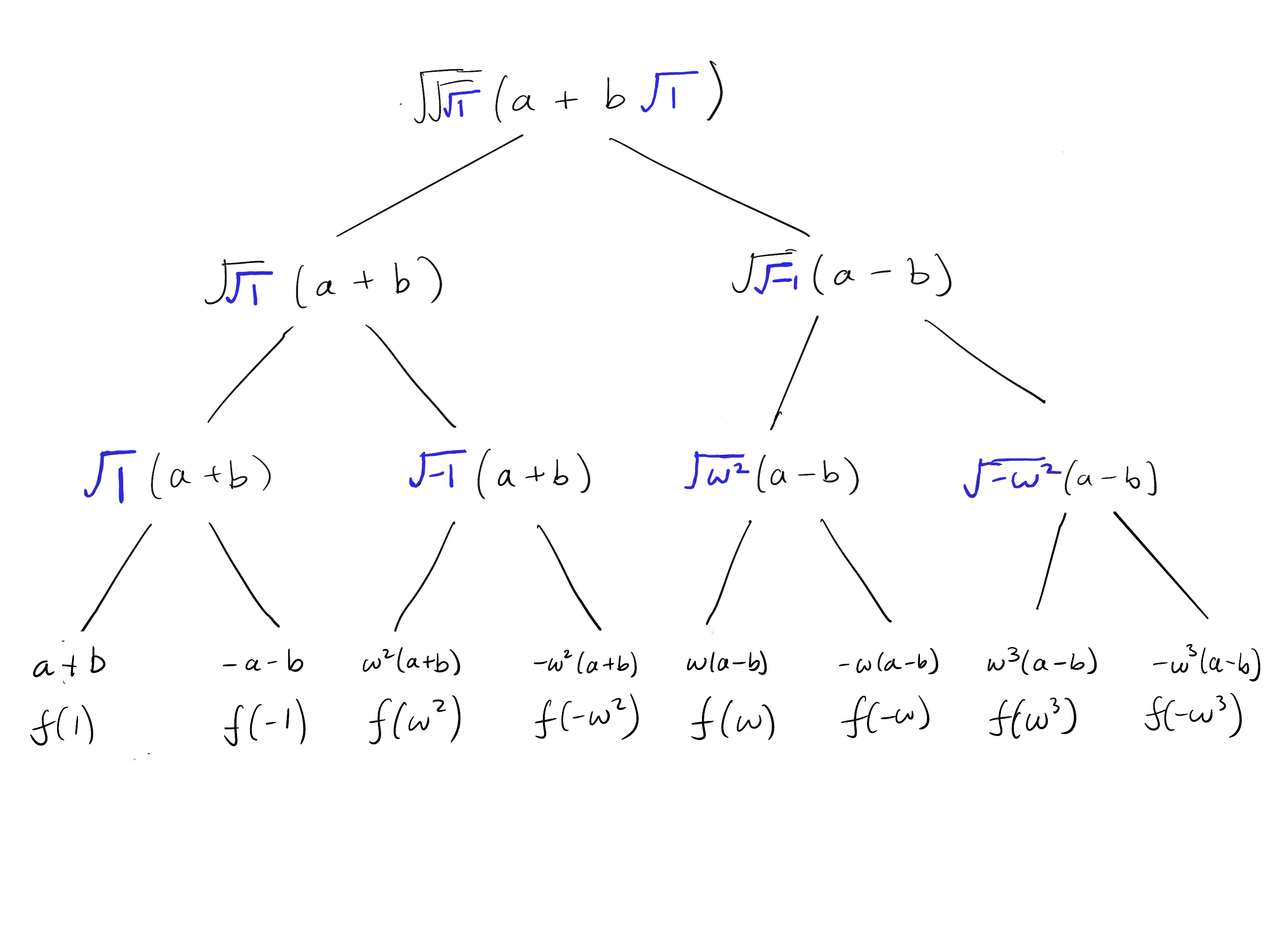

However, if we factor out first to turn into , the new form becomes a lot more manageable when we substitute for :

The first square root will disappear after the first evaluation and will become a constant for most of the tree.

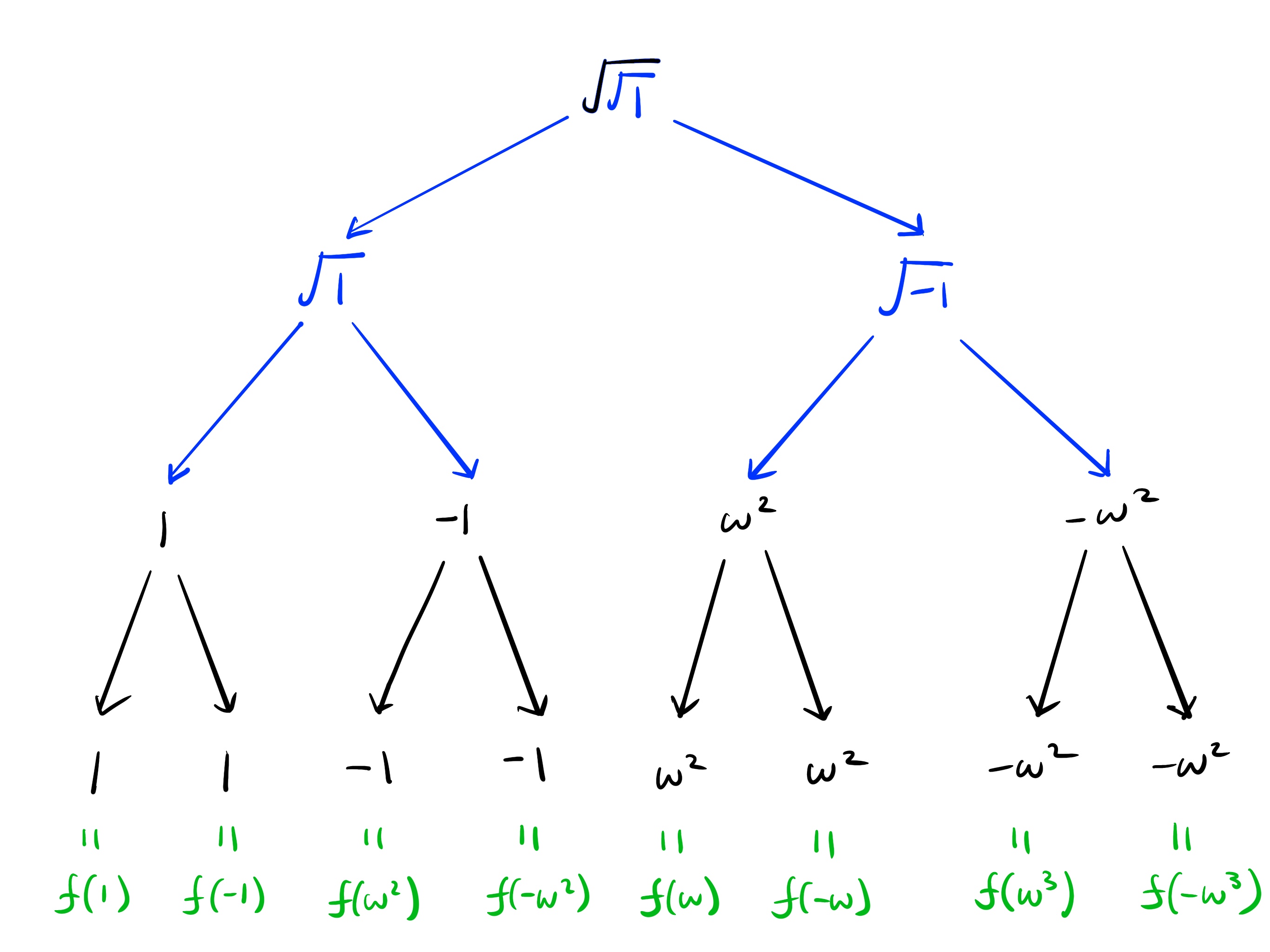

Below is a diagram of expanding the square roots. At each level, we unwrap (evaluate) one square root. The square roots in blue represent the ones evaluated at each step. As a general rule, evaluate the innermost square root if it is nested:

Now let’s compare the result to evaluating on the 8-th roots of unity one-by-one:

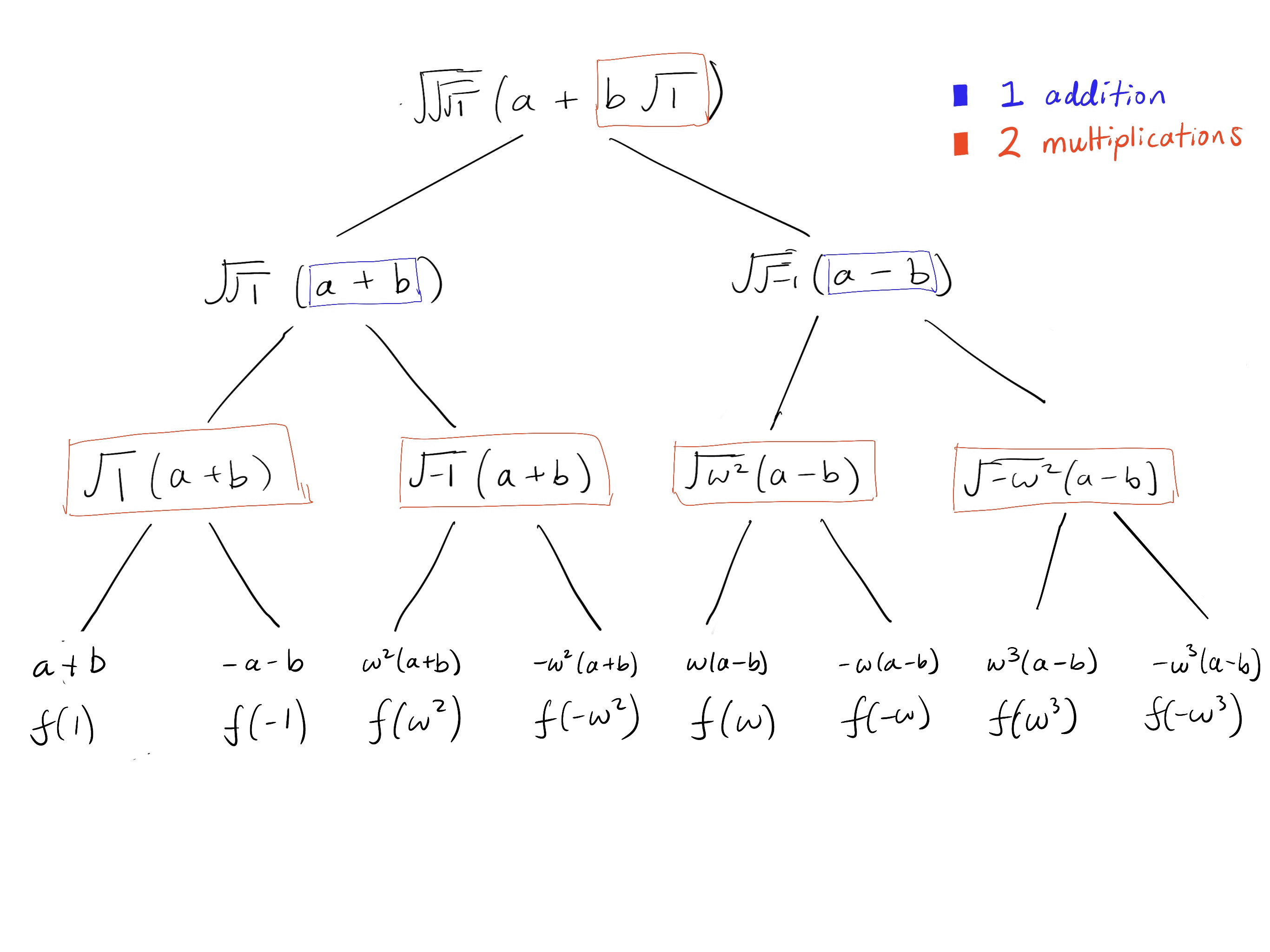

Evaluating the terms using the method above requires 8 additions and 16 multiplications.

However, using square root expansion, we only need 2 additions and 10 multiplications. Whenever a square root is expanded into its two solutions, we multiply it by the adjacent term. So whenever the “final” square root is unwrapped, it results in two multiplications. These are highlighted in red below. The additions are highlighted in blue.

Note that “computing the square root” is completely deterministic. We know it always follows the pattern of , 2nd roots of unity, 4-th roots of unity, 8-th roots of unity, and so on. Thus, there is no need to explicitly compute the square roots.

Easy terms and hard terms

We can see that terms are easiest to evaluate because they only require 1 evaluation, and the rest is just copying values down the tree.

On the other hand, with no power is the “hardest” to evaluate because we need to do a square root expansion at every step down the tree.

The nice thing about the function , which becomes the multivalued function on the -th roots of unity is that we fully evaluate the square root at the second level of the tree, and simply copy down the sum of for the rest of the evaluation.

In fact, any polynomial can be written to “maximize” the amount of terms and “minimize” the amount of terms.

Suppose we have a 7-degree polynomial that we want to evaluate on the 8-th roots of unity.

To maximize the number of terms and have only one term, we factor it as follows:

Exercise: How should the polynomial evaluated on the 4th roots of unity be factored to have only one term and as many terms as possible? Remember, is in this case.

In the next chapter, we will show how to evaluate a general degree 4 and degree 8 polynomial using square root expansion, which also happens to be exactly the NTT algorithm.

Ready to Get Started?

Join Thousands of Users Today

Start your free trial now and experience the difference. No credit card required.