Succinct proofs of a vector commitment

If we have a Pedersen vector commitment which contains a commitment to a vector as we can prove we know the opening by sending to the verifier who would check that . This requires sending elements to the verifier (assuming is of length ).

In the previous chapter, we showed how to do this with zero knowledge. In this chapter, we show how to prove knowledge of an opening while sending less than elements, but without the zero knowledge property.

Motivation

The technique we develop here will be an important building block for proving a valid computation of an inner product with a proof of size where is the length of the vectors.

In the previous chapter, we showed how to prove we executed the inner product correctly, but without revealing the vectors or the result. However, the proof is of size because of the step where the prover sends and .

The subroutine in this article will be important for reducing the size of the proof. This article isn’t concerned with zero knowledge because the previously discussed algorithm has the zero knowledge property. That is and weren’t secret to begin with, so there is no need to obfuscate them.

Problem statement

Given an agreed upon basis vector the prover gives the verifier a Pedersen vector commitment , where is a non-blinding commitment to , i.e. and wishes to prove they know the opening to the commitment while sending less than terms, i.e. sending the entire vector .

A proof smaller than

Shrinking the proof size relies on three insights:

Insight 1: The inner product is the diagonal of the outer product

The first insight we will leverage is that the inner product is the diagonal of the outer product. In other words, the outer product “contains” the inner product in a sense. The outer product, in the context of 1D vectors, is a 2D matrix formed by multiplying every element in the first 1D vector with every other element in the second vector. For example:

This might seem like a step in the wrong direction because the outer product requires steps to compute. However, the following insight shows it is possible to indirectly compute the outer product in time.

Insight 2: The sum of the outer product equals the product of the sum of the original vectors

A second observation is that the sum of the terms of the outer product equals the product of the sum of the vectors. That is,

For our example of vectors and this would be

Graphically, this can be visualized as the area of the rectangle with dimensions having the same “area” as

In our case, the vector is actually the basis vector of elliptic curve points, so we are saying that

Note that our original Pedersen commitment

is embedded in the boxed terms of the outer product:

Therefore, by multiplying the sums of the vector entries together, we also compute the sum of outer product.

Since the inner product is the diagonal of the outer product, we have indirectly computed the inner product by multiplying the sums of the vector entries together. To prove that we know the inner product, we need to prove we also know the terms of the outer product that are not part of the inner product.

For vectors of length , let’s call the parts of the outer product that are not part of the inner product the off-diagonal product.

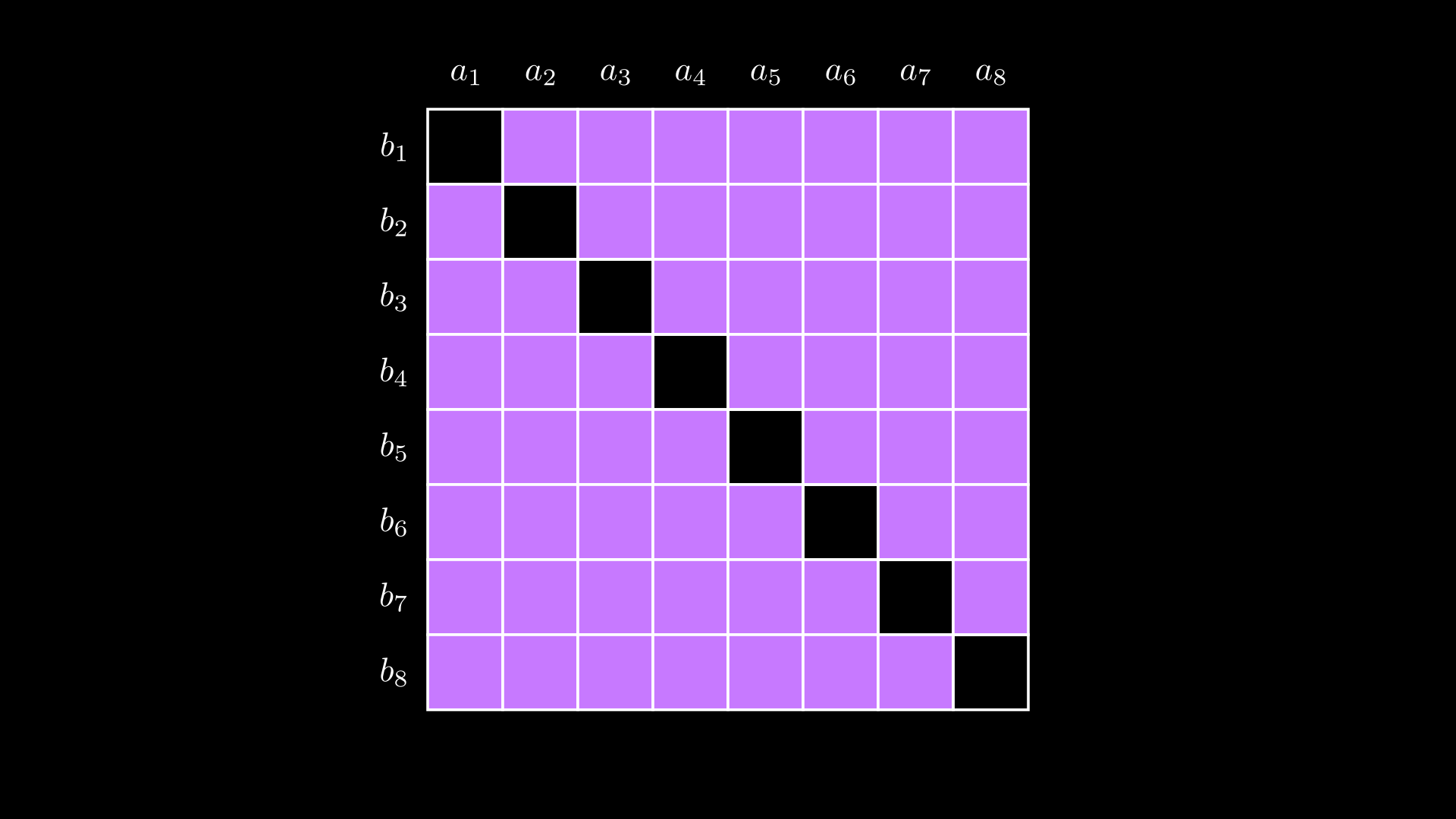

Below, we mark the terms that make up the off-diagonal product with and the terms that make up the inner product with :

We can now formally state the identity we will rely on going forward. If then:

The identity also holds if one of the vectors is a vector of elliptic curve points (even if their discrete logs are unknown).

For cases where , proving knowledge of an inner product means the prover needs to convince the verifier they know the “area” of the purple-shaded region below.

Conveying this information succinctly when is trickier, so we will revisit this later.

In the case of , the area is simply the off-diagonals.

Insight 3: If then the inner product equals the outer product

An important corner case is where we have a vector of length . In that case, the prover simply sends the verifier (which is of length ) and the verifier simply multiplies the single element of with the single element of .

Sketch of the algorithm

We can now create a first draft of an algorithm for the case that proves we have computed the inner product of and , which is equivalent to showing we know the commitment .

The interaction between the prover and the verifier is as follows:

- The prover sends their commitment to the verifier.

- The prover adds up all the terms in and sends that as to the verifier (note that the sum of the components of a vector is a scalar, hence summing the elements of results in scalar ). Furthermore, the prover computes the off-diagonal terms of (i.e. , ) and sends and to the verifier.

Graphically, and can be seen as follows:

- The verifier indirectly computes by computing where and checks that

In expanded form, the above equation is:

Note that the check above is equivalent to the identity from earlier:

Security bug: multiple openings

However, there is security issue – the prover can find multiple proofs for the same commitment. For example, the prover could chose randomly, then compute

To prevent this, we re-use a similar idea from our discussion of zero knowledge multiplication – the prover must include verifier-provided randomness in their computation. They must also send and in advance of getting so and cannot be “advantageously” selected.

The reason the prover must send and individually, instead of the sum is that the prover is able to hack the protocol by moving value between and with no restriction. That is, since

the prover could pick some elliptic curve point and compute a fraudulent and as

We need to force the prover to keep and separate.

Here is the updated algorithm that corrects this bug:

-

The prover and verifier agree on a basis vector where the points are chosen randomly and their discrete logs are unknown.

-

The prover computes and sends to the verifier :

-

The verifier responds with a random scalar .

-

The prover computes and sends :

- The verifier, now in possession of checks that:

Under the hood this is:

which is identically correct if the prover correctly computed , , and .

Note that the verifier applied to whereas the prover applied to . This causes the terms of the original inner product to be the linear coefficients of the resulting polynomial.

The fact that and are separated by , which the verifier controls, prevents a malicious prover from doing the attack described earlier. That is, the prover cannot shift value from to because the value they shift must be scaled by , but the prover must send and before they receive .

An alternative interpretation of the algorithm: halving the dimension of

The verifier is only carrying out a single multiplication, times . Even though we started with vectors of length , the verifier only carries out point multiplications.

The operation turned a vector of length into a vector of length . Hence, the prover and verifier are both jointly constructing a new vector of length given the prover’s vectors and the verifier’s randomness .

Since they have both compressed the original vector to a vector of length , the verifier can use the identity when . Here, and .

Security of the algorithm

Algorithm summary

As a quick summary of the algorithm,

- The prover sends the to the verifier.

- The verifier responds with .

- The prover computes and sends .

- The verifier checks that:

Now let’s see why the prover cannot cheat.

The only “degree of freedom” the prover has on step 3 is .

To come up with an that satisfies

the prover needs to know the discrete logs of and . Specifically, they would have to solve

where

- and are the discrete logs of and

- and are the discrete logs of and respectively, and is the discrete log of .

- and are known the prover, since the prover produced and in step 1.

However, the prover does not know the discrete logs and , so they cannot compute .

The variable has only two valid solutions

There are only two values valid for that satisfy . Note that the equation forms a quadratic polynomial with respect to variable and forms a linear polynomial. By the Schwartz-Zippel Lemma, the equation has at most two solutions. As long as the order of the field is , then the probability of the prover finding such that it results in an intersection point of is negligible.

Bulletproofs paper approach to injecting randomness

Instead of combining and together as , the prover combines them as and the verifier does . Note that the powers of the two vectors are applied in the opposite order. When we compute the outer product, the inner product terms will have the cancel:

Arguably, this approach is “cleaner” so we will use that going forward.

Introducing

The computation happens so frequently in Bulletproofs that it is handy to give it a name, which we call . The first argument is the vector we are folding (which must be of even length, if not we pad it with a ). Fold splits the vector of length into pairs, and returns a vector of length as follows:

If we do we mean:

When , is simply and .

Algorithm description with

We now restate the algorithm using the Bulletproofs paper’s approach to randomness:

- The prover sends their commitment to as to the verifier, along with and computed as

- The verifier responds with a random scalar .

- The prover computes and sends

- The verifier computes:

Assuming the prover was honest, the final check under the hood expands to:

How to handle cases when

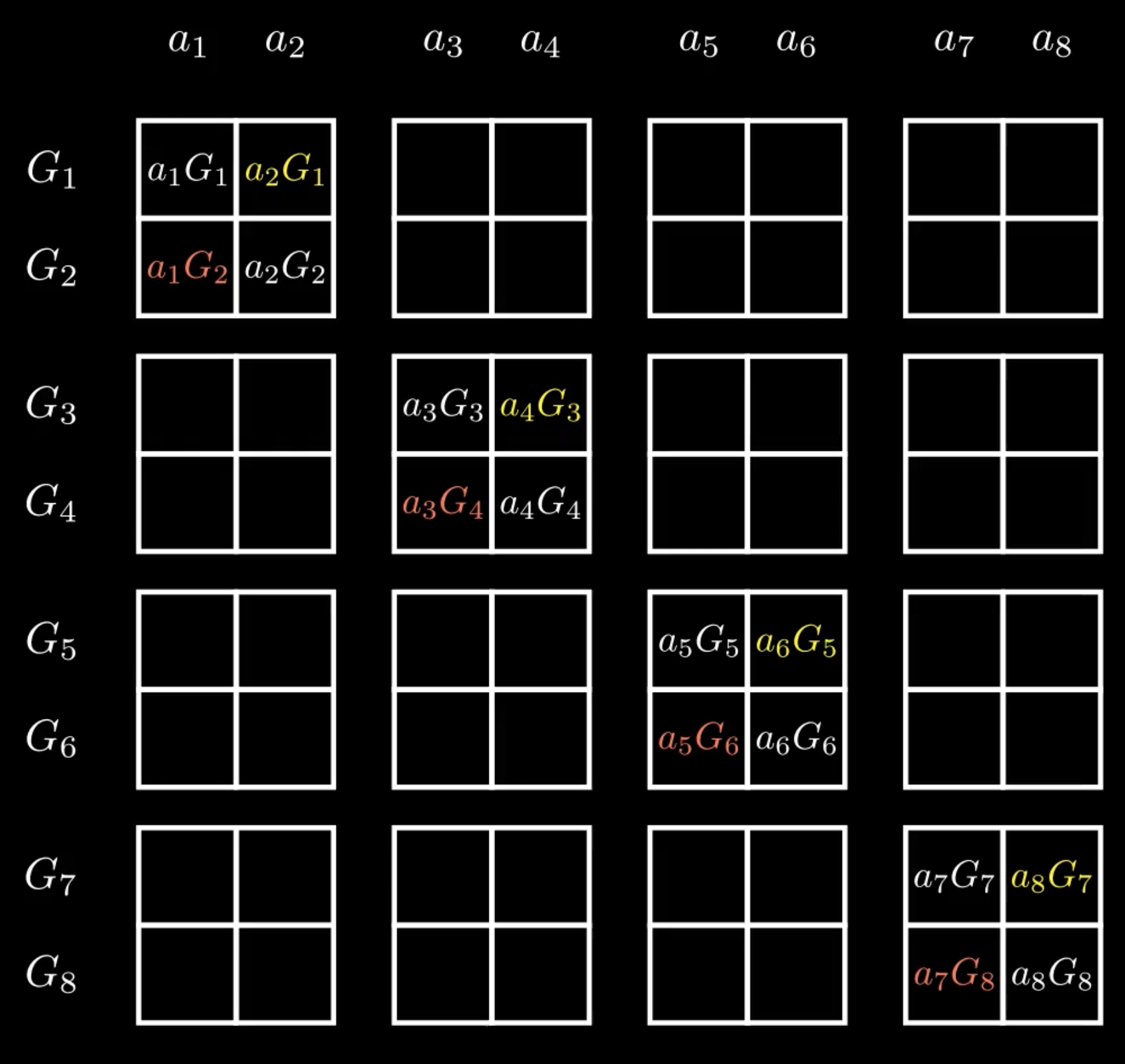

Assuming array has even length (if not, we can add a zero element to make it even length), we can pairwise-partition the array. Below is an example of a pairwise-partition:

Similarly, we can pair-wise partition .

Each of the sub-pairs can then be treated as instances of computing the inner product using the case from earlier:

We could then prove we know the four commitments , , , and and this would be equivalent to proving we know the opening to the original commitment.

However, that would create four extra terms for pairs we are proving – i.e. no efficiency gain in terms of the size of the data the prover transmits.

The naive solution would be for the prover to commit and send:

Graphically, that can be seen as follows:

As a (key!) optimization, we add up all the , and terms from each of the pairs to become the single points , , . In other words, the prover only sends:

The operation described is shown in the animation below:

Security of adding all the commitments and off-diagonals together

An initial concern with such an optimization is that since the prover is adding more terms together, there is more opportunity to hide a dishonest computation.

We now show that once the prover sends (and and ) they can only create one unique proof that they know the opening to .

Observe that is computed as and is computed as . They do not have any common elliptic curve points. Thus, the prover cannot “shift value” from to because they do not know the discrete logs of any of the points. Effectively, is a Pedersen vector commitment of to the basis vector . The security assumption of a Pedersen vector commitment is that the prover can only produce one possible vector opening. “Shifting values around” after they send the commitment would mean the prover can compute a different vector other than which produces the same commitment. But that contradicts our assumption that a prover can only produce a single valid vector for a Pedersen commitment. A similar argument can be made for .

is the addition of four Pedersen commitments (the commitments to the vectors , , , ). However, the fact that several Pedersen commitments are added together is immaterial from a security perspective. It makes no difference if the commitments are computed separately and then added, or is computed as a vector of . Consider that:

For example, the prover might “shift value” from to .

The only remaining concern is that the prover could shift value from in to in since they share a common elliptic curve point. However, this is prevented by the random from the verifier as shown previously.

Hence, once the prover sends computed in the manner described in this section, they can only create one possible opening, and thus create only one possible proof.

Proving we know an opening to while sending data

- The prover sends to the verifier. The prover also sends and .

- The verifier sends a random .

- The prover computes and sends to the verifier.

- The verifier checks that .

We leave it as an exercise for the reader to work out an example to check that the final verification check is algebraically identical if the prover was honest. We suggest using a small example such as .

Yet another interpretation of

is a commitment to the original vector with respect to the basis vector . is a commitment to the vector made up of the left off-diagonals of the pairwise outer products and is a commitment to the components of the right off-diagonals of the pairwise outer products.

The sum is itself a vector commitment of the vector to the basis , which has size .

We show the relationship graphically below:

.

In the next chapter, we show how to recursively apply this algorithm so that the prover only sends elements.

Exercise: Implement the algorithm described in this chapter. Use the following code as a starting point:

from py_ecc.bn128 import G1, multiply, add, FQ, eq, Z1

from py_ecc.bn128 import curve_order as p

import numpy as np

from functools import reduce

import random

def random_element():

return random.randint(0, p)

def add_points(*points):

return reduce(add, points, Z1)

# if points = G1, G2, G3, G4 and scalars = a,b,c,d vector_commit returns

# aG1 + bG2 + cG3 + dG4

def vector_commit(points, scalars):

return reduce(add, [multiply(P, i) for P, i in zip(points, scalars)], Z1)

# these EC points have unknown discrete logs:

G_vec = [(FQ(6286155310766333871795042970372566906087502116590250812133967451320632869759), FQ(2167390362195738854837661032213065766665495464946848931705307210578191331138)),

(FQ(6981010364086016896956769942642952706715308592529989685498391604818592148727), FQ(8391728260743032188974275148610213338920590040698592463908691408719331517047)),

(FQ(15884001095869889564203381122824453959747209506336645297496580404216889561240), FQ(14397810633193722880623034635043699457129665948506123809325193598213289127838)),

(FQ(6756792584920245352684519836070422133746350830019496743562729072905353421352), FQ(3439606165356845334365677247963536173939840949797525638557303009070611741415))]

# return a folded vector of length n/2 for scalars

def fold(scalar_vec, u):

pass

# your code here

# return a folded vector of length n/2 for points

def fold_points(point_vec, u):

pass

# your code here

# return L, R as a tuple

def compute_secondary_diagonal(G_vec, a):

pass

# your code here

a = [9,45,23,42]

# prover commits

A = vector_commit(G_vec, a)

L, R = compute_secondary_diagonal(G_vec, a)

# verifier computes randomness

u = random_element()

# prover computes fold(a)

aprime = fold(a, u)

# verifier computes fold(G)

Gprime = fold_points(G_vec, pow(u, -1, p))

# verification check

assert eq(vector_commit(Gprime, aprime), add_points(multiply(L, pow(u, 2, p)), A, multiply(R, pow(u, -2, p)))), "invalid proof"

assert len(Gprime) == len(a) // 2 and len(aprime) == len(a) // 2, "proof must be size n/2"

Ready to Get Started?

Join Thousands of Users Today

Start your free trial now and experience the difference. No credit card required.