Circle FFT — Part 1: Building the Circle Domain

Circle STARKs is a new zk-STARK scheme that has been implemented in Stwo and Plonky3, and it has been adopted by several zkVM projects. Its key innovation lies in enabling the use of small 32-bit fields (Mersenne prime ) while still maintaining the mathematical properties needed for efficient FFT operations. In this explanatory article series, we will discuss the primary algorithm behind Circle STARK, named Circle FFT.

In Part 1 article, we first review how STARK-friendly primes have evolved, and then we explore the foundational concepts of Circle FFT—namely the circle curve, its group structure, and the roles of twin-cosets and standard-position cosets, using detailed examples and derivations. Then, in Part 2 article, we will describe the Circle FFT algorithm itself in detail.

We also provide a walkthrough of these core ideas—such as the circle group and the Circle FFT—together with explicit example computations for (Mersenne prime with exponent : ) with Python-script.

Our focus is on how each of these building blocks leads into a full-fledged FFT-like routine even when does not have a large two-adic factor.

If you’re interested in running the examples yourself, the full Python code is available here, and we will reference it in later sections such as Section 4 and 6, where we walk through the group and domain construction in code.

This article was written by Yugo in collaboration with RareSkills. This article was funded by a Soulforge Grant. We are grateful for their support.

0. From STARK‑Friendly Primes to Mersenne 31

Before diving into STARK-friendly prime, let’s first recall finite-field basics.

A field is a set in which addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (except by zero) are defined. When the set of elements is finite, it is called a finite field. refers to the set of integers from up to (where is a prime), with addition, subtraction, and multiplication all taken modulo , and division defined as the inverse of multiplication modulo .

We denote by the set . Each element in has a multiplicative inverse, so can be viewed as a multiplicative group. The size of this group, , is . When we factorize into its prime factors, it is known that if a prime appears times, then there is a cyclic subgroup of size .

You can briefly illustrate this with a small prime, for example . Since factors as , there must be subgroups of sizes and . Indeed, in , the element generates a size- subgroup , and the element generates a size- subgroup .

In many STARK protocols, the Number-Theoretic Transform (NTT) or Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) relies on such a subgroup where the factor is a power of 2, so that the subgroup has size . The largest integer such that divides is called the two-adicity. A high two-adicity allows a larger power-of-2 size for FFT/NTT domains, which is key to achieving fast polynomial evaluations, interpolations, and polynomial multiplication. Moreover, implementing these NTT-based operations efficiently heavily depends on fast modular multiplications—since FFT/NTT involves repeatedly multiplying elements and reducing them modulo .

Originally, STARKs used a prime , which has a two-adicity of . In modern STARK implementations, one of the improvements was made to reduce overhead by decreasing the size of the finite field. For example, the Goldilocks field is and has a two-adicity of . Crucially, because the product of two 64-bit numbers can be split in base and reduced with only a few additions and subtractions.

What about Circle STARKs? As proposed in the Circle STARKs paper, it uses a Mersenne prime,

A Mersenne prime is a prime number of the form for some integer . Here, gives , which happens to be prime and is therefore categorized as a Mersenne prime.

One primary reason to choose is that it fits within a 32-bit machine word, making modular multiplication extremely fast. Specifically, when two 32-bit numbers are multiplied, the result is a 64-bit value, and modular reduction by can be done with only two additions.

This operation can be much faster with vectorized instructions. Modern CPUs excel at processing 32-bit integers natively, and the Mersenne 31 () fits within this architecture, allowing for optimal utilization of hardware capabilities. Compared to the 256-bit prime used in the original STARK, Mersenne 31 offers approximately 125x faster modular multiplication, and a 1.3x speedup over Baby Bear (), as discussed in Why I’m Excited By Circle Stark And Stwo by Eli Ben-Sasson.

However, the traditional FFT or NTT approach requires a large 2-adic factor in to form a sufficient power-of-2 subgroup in . Here, which has a two-adicity of only 1. Thus, we cannot directly use a large power-of-2 subgroup under multiplication.

Circle STARK still employs the Mersenne prime field . However, instead of working directly with itself, we observe that the curve

This is crucial because can include a large power of 2, creating subgroups of size . Thus, instead of working with single elements in , Circle STARK considers pairs satisfying (i.e. points on the circle curve).

By doing so, Circle STARK can implement its own fast polynomial interpolation and evaluation—often referred to as the Circle FFT—directly over these circle elements.

1. Circle Curve

Let’s move on to the core mathematics of Circle STARKs. A circle curve over a finite field is the subset of defined by all points satisfying

We sometimes denote this set by or simply “the circle.”

In the Circle STARKs, we focus on primes with (e.g., ). Under this condition, is not a square in . Concretely, this ensures that the equation has exactly solutions in and no additional outlier solutions (i.e., points at infinity). For this article, all we need is that in yields exactly points under that condition.

(However, for readers interested in a geometric perspective on why leads to exactly solutions, see the Appendix.)

1.1 Toy Example

For example, if (which is ), then is the set of all such that

Here are a few pairs in that satisfy . For example:

- and are obvious because and .

- also works because , and .

We see that there are exactly such pairs for .

2. Circle Group

This kind of set is denoted by and is often called the Circle Curve over . One striking fact is that . For example, if , then there are exactly points on the circle — notably .

This is important because in the usual STARK setting, we often want a domain of size for FFT-like operations. In the case of , having exactly 8 points on the circle means we can form subgroups of size . Later, we’ll see how this property (the high 2-adicity in ) is exploited in the Circle FFT.

A key property is that can be given with a group operation (which is, in essence, a binary operator) on its points. Specifically, we use “” to denote this operation: for two points and in ,

We can check that this group operation remains within (the result still satisfies ) and makes the set into a cyclic group of size .

2.1 Checking the Group Axioms

As the axioms of a group, we typically list the following four properties: closure, the identity element, the inverse element, and associativity. Let’s take a closer look at each one to confirm they all hold.

2.1.1 Closure

Take two points and on the circle;

Define a new point

We will show that also lies on the circle by computing step by step:

Since we know and , we substitute these values into the product:

Hence also satisfies and therefore lies on the circle. This confirms that the set is closed under the operation

2.1.2 Identity Element

The point serves as the identity element under the group operation. Concretely, for any on the circle,

One might wonder about the point . If we try to use as an identity, we see it fails:

which is not equal to for general . Because the identity element is unique, cannot be the identity.

2.1.3 Inverse

In a group, the inverse of an element is the unique point satisfying

On the circle, we see that serves as the inverse of with respect to the group operation. Indeed,

since .

Thus, the inverse of under the group operation is .

2.1.4 Associativity

The last group axiom is associativity: for any three points

on the circle,

This can be verified by expanding the polynomial, but we won’t go into detail here as it would be too long.

2.2 A Special Operation: The Squaring Map

Beyond these group axioms, there is another operation on the circle that is particularly useful in later sections, especially for the Circle FFT, namely the squaring map. This map applies the group operation to a point with itself:

Since the circle satisfies , we get , so

In the Circle FFT, we will use to halve certain evaluation domains in a recursive manner—each application of reduces the domain size by a factor of 2. This is because is compatible with the group operation. Concretely, for two points and on the circle,

This compatibility implies that maps a twin-coset of size into another twin-coset of size . We will return to this domain-halving property in detail later.

2.3 A Special Operation: The Involution

In addition to the squaring map, there is another important operation. This operation, called the involution, is defined by

Geometrically, it flips the sign of the -coordinate while leaving the -coordinate unchanged. Notice that is its own inverse—applying twice returns you to the original point:

On the circle , the involution keeps every point on the curve (since negating does not affect ). However, a point with is fixed under , meaning .

2.4 Concrete Operation of Circle Group at

In the previous concrete example, we explored with , which served as a useful toy example for building intuition. However, is too small to reveal the deeper structural properties of the Circle Group—such as longer subgroup chains or the construction of twin-cosets or standard positon coset.

Therefore, we now turn to a slightly larger prime, (which satisfies ), to illustrate these richer behaviors in a more meaningful way.

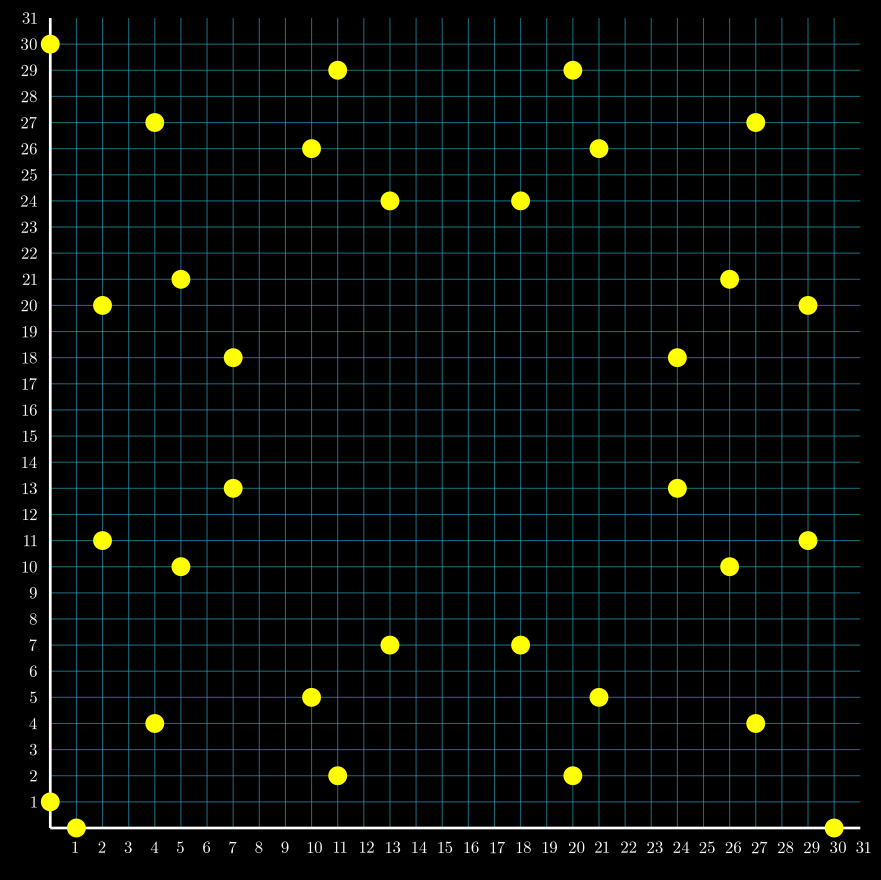

Given , which is congruent to , the set of points satisfying the equation , denoted as , is illustrated in the following diagram:

Here are a few pair examples in that satisfy :

- also works because , and .

- is also a solution: (mod 31) and (mod 31), so (mod 31).

- demonstrates that , hence (mod 31).

To see Circle Group, let us work over , where the circle has 32 points. Suppose we pick the point

We can combine with the point via the group operation:

Indeed, one verifies

so also lies on the circle .

Meanwhile, the inverse of is

because

Additionally, squaring map can work on the point . Recall that

Hence,

3. Subgroups of Circle Group

We have established that is a cyclic group of size . If is a power of two, say , then there is a nested chain of subgroups

where each has order .

In other words, is a subgroup of size 2, is size 4, and so on, up to itself, which has size .

For example, if (so ), we obtain a chain

where and each has size . A summary might look like this:

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 4 | |

| 8 | |

| 16 | |

| 32 |

Below, we explicitly list each subgroup in .

Size 1: [Point(1, 0)]

Size 2: [Point(1, 0), Point(30, 0)]

Size 4: [Point(1, 0), Point(0, 30), Point(30, 0), Point(0, 1)]

Size 8: [Point(1, 0), Point(4, 27), Point(0, 30), Point(27, 27), Point(30, 0), Point(27, 4), Point(0, 1), Point(4, 4)]

Size 16: [Point(1, 0), Point(7, 13), Point(4, 27), Point(18, 24), Point(0, 30), Point(13, 24), Point(27, 27), Point(24, 13), Point(30, 0), Point(24, 18), Point(27, 4), Point(13, 7), Point(0, 1), Point(18, 7), Point(4, 4), Point(7, 18)]

Size 32: [Point(1, 0), Point(2, 11), Point(7, 13), Point(26, 10), Point(4, 27), Point(21, 5), Point(18, 24), Point(20, 29), Point(0, 30), Point(11, 29), Point(13, 24), Point(10, 5), Point(27, 27), Point(5, 10), Point(24, 13), Point(29, 11), Point(30, 0), Point(29, 20), Point(24, 18), Point(5, 21), Point(27, 4), Point(10, 26), Point(13, 7), Point(11, 2), Point(0, 1), Point(20, 2), Point(18, 7), Point(21, 26), Point(4, 4), Point(26, 21), Point(7, 18), Point(2, 20)]

4. Python Code 1: Circle Group

We will now review the Circle Group code through the Simple Python implementation. Only the most important functions or parts are described here, and all code is available here.

Here, we define two key classes-FieldElement and CirclePoint—to handle arithmetic in the underlying finite field and group operations on the curve, respectively.

4.1 FieldElement

First, the FieldElement class defines arithmetic operations in the finite field , such as addition, multiplication, and inversion modulo 31. This is the foundation for all computations on the circle curve.

# Mersenne 5

MOD = 31

class FieldElement:

def __init__(self, value):

"""Initialize a field element"""

self.value = value % MOD

def __add__(self, other):

"""Add two field elements"""

return FieldElement((self.value + other.value) % MOD)

def __mul__(self, other):

"""Multiply two field elements"""

return FieldElement((self.value * other.value) % MOD)

def inv(self):

"""Compute the multiplicative inverse"""

return FieldElement(pow(self.value, MOD - 2, MOD))

def square(self):

"""Compute the square"""

return self * self

4.2 CirclePoint

The CirclePoint class represents points on the circle curve . The add method implements the group operation, while double applies the squaring map.

class CirclePoint:

def __init__(self, x, y):

"""Initialize a point on the circle x^2 + y^2 = 1"""

if (x.square() + y.square()).value != 1:

raise ValueError("Point does not lie on the circle")

self.x = x

self.y = y

def add(self, other):

"""Perform group operation: (x1,y1)・(x2,y2) = (x1*x2 - y1*y2, x1*y2 + x2*y1)."""

nx = self.x * other.x - self.y * other.y

ny = self.x * other.y + other.x * self.y

return CirclePoint(nx, ny)

def double(self):

"""Apply squaring map: π(x,y) = (2*x^2 - 1, 2*x*y), since x^2 + y^2 = 1."""

xx = self.x.square().double() - FieldElement.one()

yy = self.x.double() * self.y

return CirclePoint(xx, yy)

@classmethod

def identity(cls):

"""Return the identity element (1, 0) of the circle group."""

return cls(FieldElement.one(), FieldElement.zero())

Then you can simulate a Circle Group operation example as described in section 2.4.

For instance, adding CirclePoint and CirclePoint results in Point .

p1 = CirclePoint(FieldElement(13), FieldElement(7))

p2 = CirclePoint(FieldElement(30), FieldElement(0))

# group operation

p3 = p1.add(p2)

print(f"p1・p2 = {p3}")

p1・p2 = Point(18, 24)

Doubling yields

# squaring map

p1_double = p1.double()

print(f"π(p1) = {p1_double}")

π(p1) = Point(27, 27)

The inverse of is , and adding them gives the identity

# Inverse

p1_inv = p1.inverse()

print(f"p1's inverse = {p1_inv}")

p1_plus_inv = p1.add(p1_inv)

print(f"p1・p1_inv = {p1_plus_inv}")

p1's inverse = Point(13, 24)

p1・p1_inv = Point(1, 0)

4.3 Circle Group

The function generate_subgroup generates a subgroup of order . It obtains the appropriate generator from the get_nth_generator function and repeats the group operation add to construct the subgroup.

def generate_subgroup(k: int) -> list[CirclePoint]:

"""Generate a subgroup of size 2^k using the generator."""

g_k = get_nth_generator(k)

p = CirclePoint.identity()

return [ (p := p.add(g_k)) if i else p

for i in range(1 << k) ]

For example, you can get size 8 subgroup.

G3 = generate_subgroup(3)

Size 8: [Point(1, 0), Point(4, 27), Point(0, 30), Point(27, 27), Point(30, 0), Point(27, 4), Point(0, 1), Point(4, 4)]

5. Coset, Twin-Cosets and Standard Position Cosets

Twin-Cosets and Standard Position Cosets are the domains in Circle STARKs. Let’s briefly review how domains are used in traditional STARKS before understanding the mathematical properties of twin-cosets and standard position cosets. As discussed in Section 0, traditional STARKS typically utilized multiplicative (sub)groups represented as as their domains. These domains served two primary purposes.

Firstly, they acted as the evaluation domain when constructing polynomials from the computation trace via IFFT, and we have to conduct the Low Degree Extension (LDE) with the extended domain via FFT and also we construct constraint polynomials and evaluate them on LDE.

Secondly, in Low Degree Testing, particularly with FRI commitments, polynomials must be evaluated via FFT over domains that are iteratively halved during the recursive FRI folding steps.

In addition, during the FRI folding steps, as the degree of the polynomial was halved, the size of the domain also needed to be halved. Halving the domain size is central to both FRI and FFT. Keep this in mind as we proceed.

Because while the circle group itself already offers high 2-adicity, the construction of Twin-Cosets or Standard Position Cosets ensures that, during recursive squaring steps in the FFT, the evaluation domains (i.e., the Twin-Cosets or Standard Position Coset) can also be halved in size while preserving their coset structure. This is essential for enabling FFT-style operations over these domains in each level of the recursion.

5.1 Coset

Let us recall the definition of a coset in group theory. Suppose is a subgroup of a group , and let . Then the left coset of by is the set

If , then . Otherwise, in case of , is a disjoint set from , but still has the same size as . This holds because if , ’s closure under the group operation ensures , while if , no element of can be in without implying , and the bijection preserves the size.

In our particular setting, , which is cyclic of size . From the previous section, we know there is a chain of subgroups with .

Hence, for instance, if we fix of order , then for any point on the circle, the coset

is called a coset of .

That set will have the same cardinality , and is disjoint from itself unless already belongs to .

5.1.1 Coset Example

Let’s illustrate this example quickly. In the case , recall that , so there is a chain of subgroups where . Concretely,

Now take a point not in . For instance,

Since is not in , the set

will be a distinct coset of , disjoint from itself.

Hence,

which indeed has size 2. This is the coset of corresponding to , clearly different from the subgroup itself.

5.2 Twin-Cosets

We now define a twin-coset by taking the union of two cosets: and its inverse coset . Concretely, let

We say that is a twin-coset of size if the following conditions hold:

-

Disjointness

The two cosets and are disjoint.

In practice, this disjointness is equivalent to ensuring . This equivalence arises from the properties of cosets. If , then would be in both and (overlap). Conversely, if the cosets don’t overlap, then cannot be written as (for any ), which implies . -

No fixed points under the involution

A point is called a fixed point of a map if . In our case, we consider the involution

If contained any point where , then would remain unchanged. It is a fixed point. We want to avoid having such points in , because by definition a twin-coset excludes any fixed points of .

Under these conditions, each coset and has distinct points, giving a total of points in . Intuitively, we merge a coset with its inverse coset, forming a domain of elements.

5.2.1 Twin-Coset Example

Continuing from the coset example in Section 5.1.1 (where we picked not in ), let us now form a twin-coset of size . We already saw:

Next, compute and form the coset :

Hence,

Taking the union, the twin-coset is:

This domain has size 4 and satisfies the twin-coset conditions: the two cosets are disjoint (since ), and contains no point with , so there are no fixed points under the involution . Thus, is indeed a twin-coset of size .

5.3 Standard Position Cosets

A standard position coset is a special kind of twin-coset of size which also coincides with a single coset of the subgroup :

Here, recall that is the unique subgroup of of order , as introduced earlier in Section 3. We have a chain of subgroups:

and each is of size . So, contains , and we will relate the cosets of these subgroups using a point of order .

Let’s unpack this step by step:

First, since , we can view as consisting of two disjoint cosets of , namely:

If we now multiply this by a fixed point of order , we obtain:

It turns out that , so:

Therefore, the coset can be written as the union of two disjoint cosets: one by , the other by , each over the smaller subgroup . This is exactly the definition of a twin-coset.

But not all twin-cosets arise in this way. To ensure this construction works properly, we require:

- Disjointness: . Otherwise, the two cosets would overlap.

- No fixed points under involution: The resulting set must avoid points with , so the involution has no fixed points in .

- Correct order: must have order to guarantee that spans exactly distinct elements.

When these are satisfied, the coset gives a standard position coset: a domain of size that is simultaneously a twin-coset and a single coset of a larger subgroup.

5.4 Hand-Computed Example: Twin-Cosets and Standard Position Cosets at

Below, we illustrate how the notions of twin-cosets and standard position cosets apply when We have , so subgroups exist, where and . We will show the standard position coset for that is .

5.4.1 Twin-Coset Construction

-

Setup

Let . Then has size 4. Pick a point of order 16 (so , but ). Concretely, one may choose -

Forming the Twin-Coset

Since has the four points , , , and , each point is multiplied by or .

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

Combining these gives 8 distinct points. No element of is fixed by , so is a twin-coset of size . Combining these gives 8 distinct points. No element of is fixed by , so is a twin-coset of size .

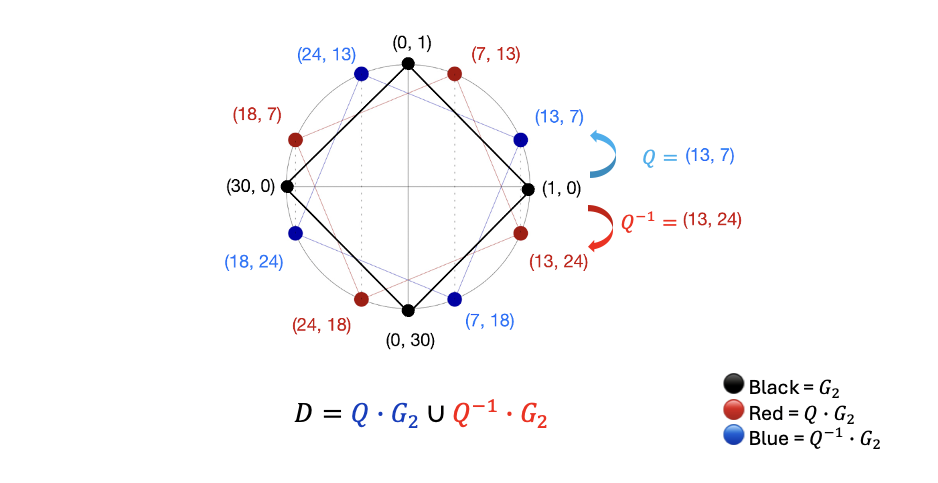

In the diagram below, 🔴 red points represent and 🔵 blue points represent . Together, they form the 8-point twin-coset .

5.4.2 Checking Standard Position coset

This same also equals for some subgroup of size 8, meaning is a standard position coset.

is the subgroup , then multiplying each element by yields exactly the 8 points in .

Hence

Because is both a twin-coset of and a single coset of , we call it a standard position coset of size 8.

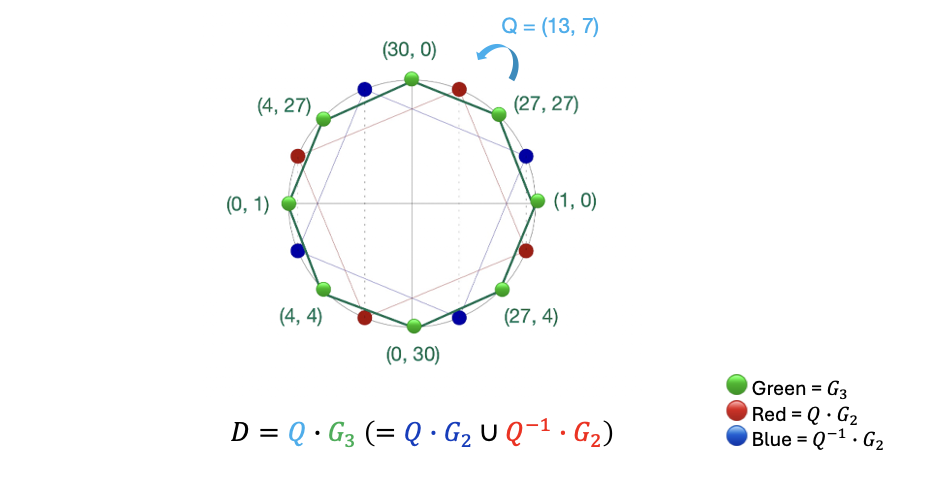

In the diagram below, 🟢 green points represent the subgroup , 🔴 red and 🔵 blue points represent the two disjoint cosets and , respectively. Their union forms the twin-coset , and the entire 8-point set constitutes the standard position coset .

Thus, whenever has order , we can build a standard position coset of size . This structure is important in Circle STARK, as it provides a neat domain of points even if is not sufficiently two-adic.

6. Python Code 2: Circle Domain

We will now review the Circle Domain code through the Simple Python implementation. The domain construction (such as twin-coset and standard position coset) is also implemented in the same Python notebook. You can run and inspect how these sets are built step-by-step.

6.1 Twin-Coset

This function generates a domain by applying group operations add to and its inverse over the subgroup, ensuring symmetry and size .

def generate_twin_coset(Q, G_n_minus_1):

"""Generate twin-coset: D = Q・G_(n-1) ∪ Q^{-1}・G_(n-1)."""

Q_inv = Q.inverse()

coset_Q = [Q.add(g) for g in G_n_minus_1]

coset_Q_inv = [Q_inv.add(g) for g in G_n_minus_1]

return coset_Q + coset_Q_inv

G2 = generate_subgroup(2)

Q = CirclePoint(FieldElement(13), FieldElement(7))

twin_cosets = generate_twin_coset(Q, G2)

print(twin_cosets)

[Point(13, 7), Point(7, 18), Point(18, 24), Point(24, 13), Point(13, 24), Point(24, 18), Point(18, 7), Point(7, 13)]

6.2 Standard Position Coset

This function generates the standard position coset by applying group operation add for and subgroup.

def generate_standard_position_coset(Q, G_n):

"""Generate standard position coset D = Q・G_n."""

return [Q.add(g) for g in G_n]

G3 = generate_subgroup(3)

Q = CirclePoint(FieldElement(13), FieldElement(7))

D = generate_standard_position_coset(Q, G3)

[Point(13, 7), Point(18, 7), Point(7, 18), Point(7, 13), Point(18, 24), Point(13, 24), Point(24, 13), Point(24, 18)]

This kind of code, you can check the equality of standard position coset

D_std = generate_standard_position_coset(Q, G3)

D_twin = generate_twin_coset(Q, G2)

print("Q・G3:", D_std)

print("(Q・G2) ∪ (Q^-1・G2):", D_twin)

if set(D_std) == set(D_twin):

print("Equal: standard position coset Q·G3 = Q·G2 ∪ Q^-1·G2")

else:

print("Not Equal")

7. Decomposition of a Larger Standard Position Coset into Smaller Twin-Cosets

In many steps of the Circle FFT and FRI, we need to manage evaluation domains of different sizes, all of which lie on the circle curve. One key method to achieve this is Lemma 2 from the Circle STARKs paper, which ensures that a standard position coset of size can be broken down into smaller twin-cosets of size for any .

7.1 Statement of Lemma 2

Let be a standard position coset of size . Then for any , one can decompose into twin-cosets of size . Concretely, if

then

In simpler terms, if is a standard position coset of size , we can slice it into smaller twin-cosets (each of size ) using powers of . This partitioning allows one to make precisely the parts of that are needed in a given step of the Circle FFT protocol.

7.2 Hand-Computed Example: Splitting a Size- standard position coset into 2 Twin-Cosets of Size

Suppose , so . We have subgroups , where .

- Our standard position coset

Let with . Here, has order , meaning but forms a coset of size .

- Goal

Break into twin-cosets of size . Let , so and .

Then Lemma 2 suggests

Because , we have and .

7.2.1 Case

- .

- .

Compute:

Thus, the first twin-coset has 4 distinct points.

7.2.2 Case

- .

That is . - Likewise, .

Again, multiply each by and :

This yields another 4 points, forming the second twin-coset of size 4.

7.2.3 Union of the Two Twin-Cosets

Taking the union of both 4-point sets (for and ) recovers the entire 8-element coset . Hence:

This exactly matches the statement of Lemma 2, showing how an 8-point standard position coset can be decomposed into two twin-cosets each of size 4.

7.3 Hand-Computed Example: Splitting a Size- standard position coset into 4 Twin-Cosets of Size

And we can also divide this size-8 standard position coset into multiple smaller twin-cosets.

Let , so . Lemma 2 gives:

Since , each twin-coset has 2 points:

- :

- : $

={(24, 13), (24, 18)}$ - : ${Q^9 \cdot G_0 = Q^9, Q^{-9} \cdot G_0 = Q^{-9}}

$ - : $

={(7, 18), (7, 13)}$

This decomposes into four twin-cosets of size .

8. Squaring Map Halves a Twin-Coset

While Lemma 2 focuses on splitting large cosets into smaller twin-cosets, Lemma 3 exploits a squaring map to halve the size of a twin-coset. This process is used for the domain halving steps in Circle FFT, where we iteratively reduce the domain size.

8.1 Statement of Lemma 3

This lemma appears in the Circle STARKs paper, where it is used to formalize the recursive domain halving enabled by the squaring map.

Suppose is a twin-coset of size (with ). Then applying the squaring map transforms into another twin-coset of size . Moreover, if was a standard position coset, then also remains a standard position coset.

Intuitively, is a group endomorphism, and it maps a subgroup into . Hence, a twin-coset of size naturally yields another twin-coset of size .

8.1.1 Abstract View of Lemma 3’s Proof

Let be a twin-coset of size , which in an abstract notation means

where .

In particular, maps the subgroup onto due to a group endomorphism.

This is exactly the definition of a twin-coset in the subgroup , which has size . Accordingly, is itself a twin-coset of size .

If was originally a standard position coset, then applying preserves that standard position property, because . Thus is again a standard position coset, but now of size .

8.2 Hand-Computed Example (Halving a Size- Twin-Coset to Size )

Assume and let be a twin-coset of size . Concretely,

Since , we have . We check how affects :

8.2.1 Computing and

8.2.2 Applying to

The subgroup has size 2, say . By Lemma 3,

$$

\begin{align*}

\pi(Q)\cdot(1,0) &= (27,27)\

\pi(Q)\cdot(30,0) &= (4,4)\

\pi(Q^{-1})\cdot(1,0) &= (27,4)\

\pi(Q^{-1})\cdot(30,0) &= (4,27)

\end{align*}

\cup

{(27,4), (4,27)}$$

which is a twin-coset of size 4.

Thus, halves from 8 elements to 4, exactly as Lemma 3 states. Repeated application of continues to shrink the domain in powers of 2, playing a critical role in the recursive structure of the Circle FFT.

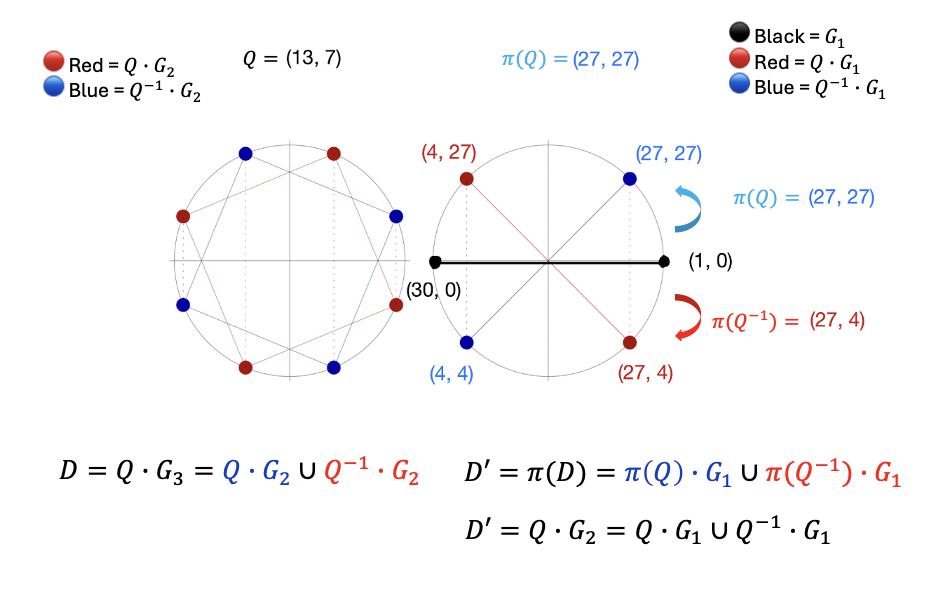

In the diagram below:

- The left circle shows the original twin-coset , where 🔴 red = and 🔵 blue = .

- The right circle shows the halved twin-coset , where 🔵 blue = and 🔴 red = .

- ⚫ Black points mark the subgroup .

This visual illustrates how maps the original domain of size into a new twin-coset of size via group endomorphism.

9. What We Built in Part 1

In this article, we focused on how the circle curve over can be turned into a cyclic group of size , and we discussed twin-cosets and standard position cosets with concrete examples. We also showed two key techniques: one for splitting a larger standard position coset into smaller twin-cosets, and another for halving the size of a twin-coset by applying the squaring map. Together, these techniques let us reshape domains of size at will.

In the next part, we will dive deeper into the Circle FFT itself, showing how these -sized domains—together with the ability to split or halve them—enable fast polynomial evaluation and interpolation, even when is not sufficiently two-adic.

References

- Circle STARKs

https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/278 - Plonky3

https://github.com/Plonky3/Plonky3 - ZK11: Circle STARKs - Ulrich Haböck & Shahar Papini

https://youtu.be/NAhLYMysSdk?si=OlzNKS1DSTRkPnUR - Circle STARKs: Part I, Mersenne

https://blog.zksecurity.xyz/posts/circle-starks-1/ - Why I’m Excited By Circle Stark And Stwo

https://starkware.co/integrity-matters-blog/why-im-excited-by-circle-stark-and-stwo/ - Exploring circle STARKs

https://vitalik.eth.limo/general/2024/07/23/circlestarks.html - An introduction to circle STARKs

https://blog.lambdaclass.com/an-introduction-to-circle-starks/ - Yet another circle STARK tutorial

https://research.chainsafe.io/blog/circle-starks/ - Deep dive into Circle-STARKs FFT

https://ihagopian.com/posts/deep-dive-into-circle-starks-fft - Coset’s Circle STARKs lecture videos

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLbQFt1T_44DyihAOawprEABRPWgYeXB5u&si=AJe0dP7FUfp2Bebe - Ethereum/research/circlestark(Python implementation)

https://github.com/ethereum/research/tree/master/circlestark - Rust Implementation Demo of Circle Domain and Circle FFT

https://youtu.be/ur3c4mIi1Jc?si=lxU10mZ6vOFCrzvw

https://github.com/0xxEric/CircleFFT - STARKの原理

https://zenn.dev/qope/articles/8d60f77e3a7630

Appendix

Below, we introduce the Projective vs Affine view of the circle curve, and then explain why Circle STARKs specifically chooses primes to avoid projective complications like points at infinity.

A.1 Projective and Affine

In an affine plane over , a point is simply written as with . By contrast, in the projective plane , each point is denoted by , but all nonzero scalar multiples represent the same location. Formally,

- When , we can re-scale by dividing each coordinate by , giving an affine point .

- When , we get a point at infinity, which has no affine counterpart.

A.2 Why Avoid Points at Infinity?

To see how points at infinity arise, rewrite in projective form:

Here, if , we regard and , so becomes .

A point at infinity is any solution with . Whether such solutions exist depends on whether is a square in :

- For example, if , then is a square in .

Concretely, there is some with , implying can have nonzero at .

This yields extra infinite points on the circle, complicating group operations and implementation.

Example:- Here, in , and is indeed .

- So admits nonzero at , giving two points at infinity.

- The affine equation has exactly four affine solutions:

- And the projective points at infinity are

, there are solutions in total — matching (affine + infinite ). - If , then is not a square in .

Consequently, has no nonzero solutions at . We get no points at infinity, and all solutions remain affine.

Example:- Since is not a square (we have and ), no satisfy at .

- The equation then has only affine solutions. Checking yields:

for a total of solutions, matching .

In Circle STARK, we specifically choose so that is not a square in . This ensures our circle has no infinite (projective) points, keeping every solution in affine coordinates and avoids the complexities of handling points at infinity.

Ready to Get Started?

Join Thousands of Users Today

Start your free trial now and experience the difference. No credit card required.